[Editor’s Note: This is the second installment for the week of October 14th through the 20th, the week which Colleen and I traveled solo separately (or is it separately solo?). Colleen’s adventures in Rishikesh were published a few days ago and this installment covers what I (Ritchard) was up to while Colleen was at Baby Slo-Mo Sleep-Away Yoga Camp. (Hey, while the cat’s away…)

Back when we set our overall itinerary for India, we had allowed 6 days, between Rajasthan and Kolkata in a place called Rishikesh where Colleen planned on going to a yoga retreat and I would (presumably) find some other way of amusing myself for six days. I tried yoga once with Colleen and, while I enjoyed the physical component of it, I just didn’t care for the setting, so going to the retreat with Colleen (some couples do it) wasn’t ever really an option. Upon considering what I would do for six days in Rishikesh on my own, I quickly realized that I would, in fact, be on my own which in turn led to the realization that I didn’t necessarily have to spend that time in Rishikesh. And so I considered where I might want to be instead.

Insofar as where to go, my first inclination (largely because we had nixed Nepal from our itinerary) was to get as close to the Himalaya mountains as I could, so I started looking north and west of Rishikesh when I came across the city of Chandigarh, which resonated for a couple of reasons. First of all, Chandigarh is kind of a legendary place among at least some architects as it is a “new city” which was planned by Le Corbusier, one of the Masters of the Modern Architectural Movement. And, while Chandigarh is not in the Himalayas, it appeared possible to at least get into the Himalayan foothills from there.

While the prospect of travelling solo and letting my inner Architect shine or roar or whatever was pretty exciting to think about, the thought of travelling without Colleen, my constant travel companion through thick and thin for the past 10 months (really my entire life) seemed a bit unsettling. We had a somewhat similar experience in 2021 following Collen’s retirement when, after three weeks of travelling in Turkey, I returned to the States while Colleen continued to Sri Lanka for a three week yoga retreat, but I was safe and sound at “home” then, not also travelling in remote cities.

And so, I looked forward to my stay in Chandigarh with both excitement and maybe also a little bit of trepidation.

One word of warning to the reader. For better or worse, I went down a bit of an architectural rabbit hole on this one. While I have tried to present what follows in terms which are understandable to non-architects (i.e., normal people), much of the content relates to issues of urban planning and architectural design issues which may or may not actually be of interest to everyone. My apologies in advance if I’ve failed to present them in such a way as to capture yours and, if I didn’t, I’ll try to do better the next time. Thanks

Chandigarh (The Ideal)

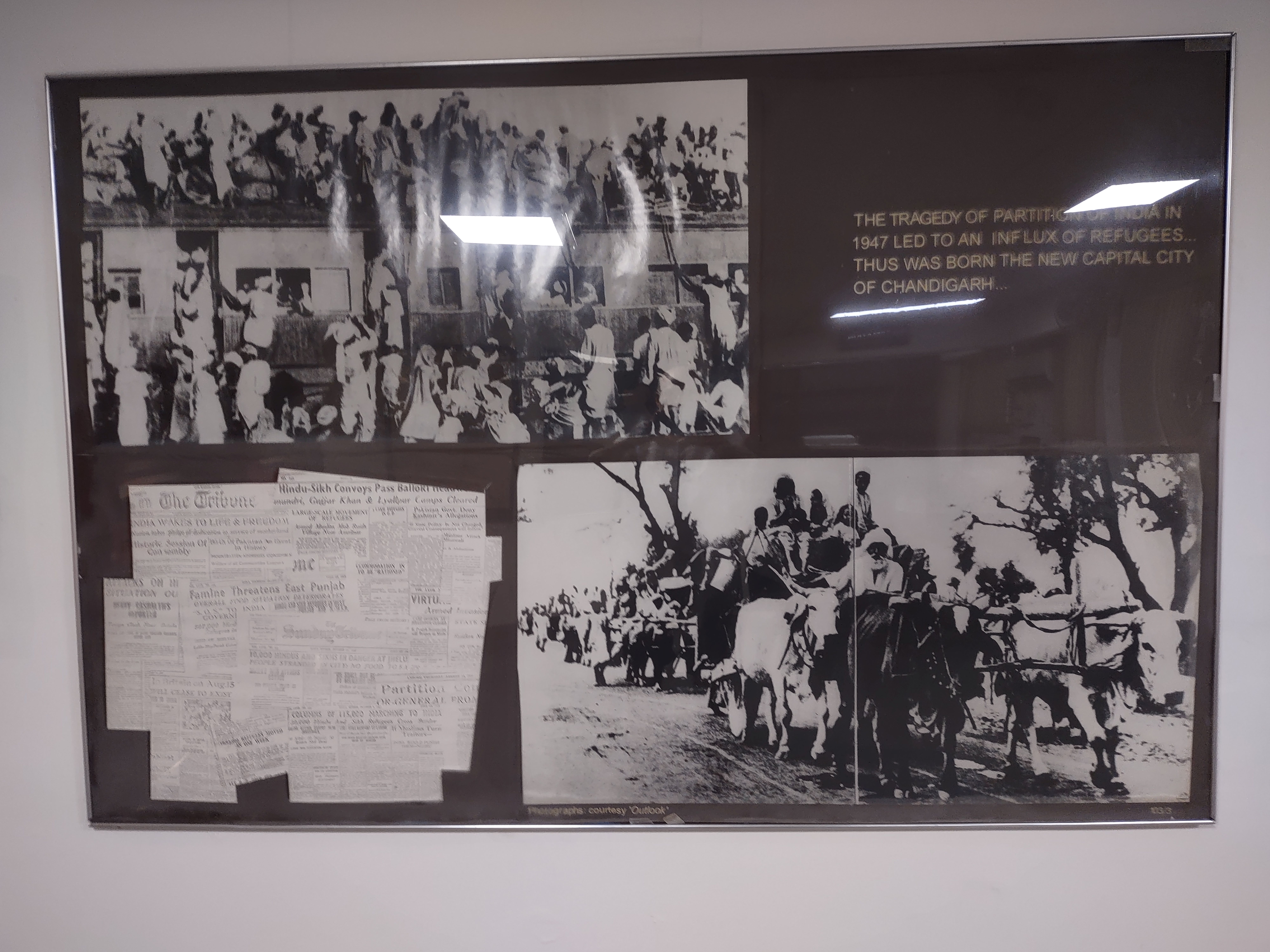

The city of Chandigarh, named after the goddess Chandi and known as “The City Beautiful”, came into being on the heels of Indian independence in 1947. As a result of “The Partition” (as the separation of India and Pakistan is commonly known), Lahore, the much beloved previous capital of the Indian state of Punjab, became a part of the new Pakistan, a tragic and heart rending event for all involved (watch Midnight’s Children) and therefore, a new capital was needed. Consideration was given to other existing cities in Punjab, but none were believed to have a desirable location nor the necessary resources to support the anticipated number of emigrees and refugees, so the decision was made to build a new Capital city.

This was seen as a great opportunity by Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Indian Prime Minister, to create a new city which would physically manifest the vision and aspirations of the new country of India and become a model of what India’s future could be. In Nehru’s words: “Let this be a new town, symbolic of the freedom of India, unfettered by the traditions of the past, an expression of the nation’s faith in the future…”.

In 1948 a site was identified for the new Capital city in a gently sloping valley south of the Shivalik range of the Himalaya foothills between two seasonal rivulets. The site was selected due to is central location in the State, its proximity to the national capital, and because it has good drainage, a good natural water supply, fertile soil, a beautiful backdrop of hills, and a favorable climate.

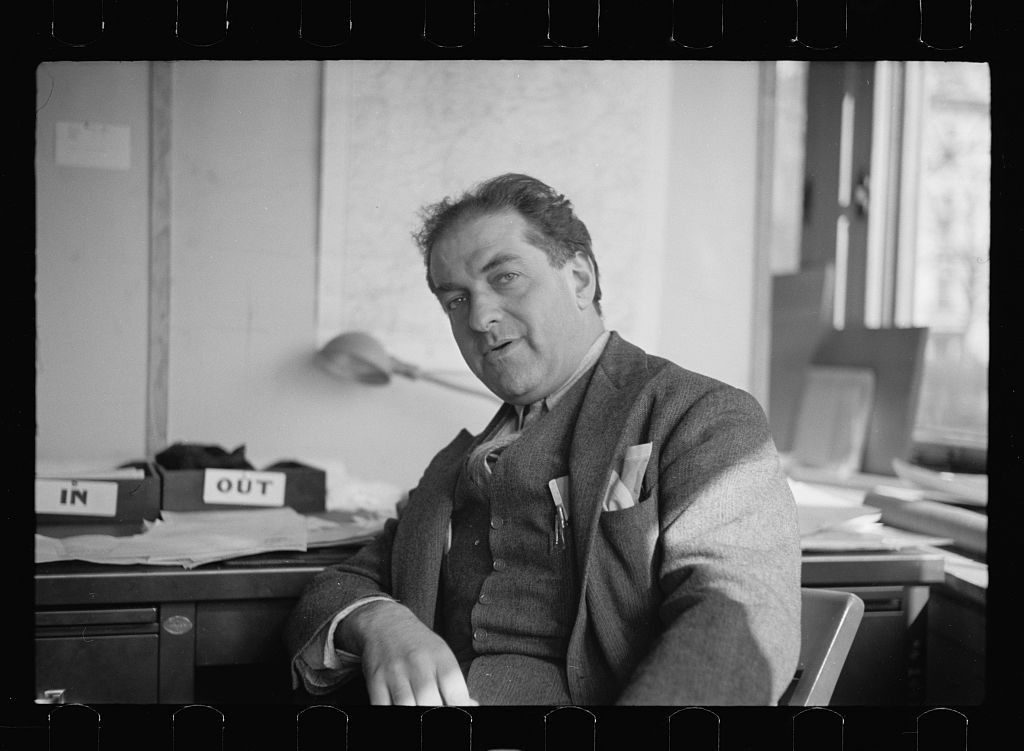

Nehru felt that Indian planners and architects lacked the necessary experience for this undertaking and so turned to Western planners and architects, which remains a bit of a point of controversy to this day. Initially, American Albert Mayer of New York City, a civil engineer turned architect with international planning experience in Israel and India, was selected to design the new Capital city.

But after the freak and tragic death of Mayer’s chief partner, Polish architect Maciej Nowicki (he died in a TWA airline crash near Cairo while returning from Chandigarh), the Indian government decided to pivot and an international search was undertaken for another planner/architect to lead the project.

[Side Note: While visiting the Chandigarh Architecture Museum where the planning process is meticulously documented and exhibited, I had the opportunity to see the various letters of nomination and recommendation for a new Master Planner which included a field of well-known international architects of the time (1950) as well as at least one nomination of the Spanish artist Pablo Picasso. To the best of my knowledge, Picasso never designed an actual building, but his painting certainly includes Cubist architectural imagery and his work had a strong influence on many modernist architects including Le Corbusier and, more recently, in the work of American architect Frank Gehry (one of my personal favorites). One can only wonder what Chandigarh might have become had Picasso been selected…]

In any case, after consideration of numerous candidates and an interview process, Swiss-French architect Charles Eduard Jeanneret (known as Le Corbusier) of France was chosen to lead the planning team which included his cousin, Pierre Jeannerate, and a British wife-husband architect team of Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry who were known for their modernist design work in tropical climates. Le Corbusier is considered to be one of the Modern Masters of Architecture and both his minimalist approach and aesthetic of architecture as the play of light on volumes and surfaces continues to have a profound effect on architecture students and influence on the work of architects around the world.

Le Corbusier (“Corbu” among architectural students) also had some very utopian ideals regarding urban living which likely resonated with Nehru, but up until this rather late point in Corbusier’s career, had only been explored in his Unite d’Habitation projects, enormous residential blocks for about 1,500 occupants in Paris and Marseilles, which he undertook in the 1940’s. (Frankly, a little scary to imagine an entire city of these.)

For Corbusier, Chandigarh represented the opportunity of a lifetime to put his social theories on urban living into practice at an unprecedented scale. Additionally, Le Corbusier was responsible for the planning and design of a new Capital Complex and he and his team were also responsible for the architectural control and design of the major buildings of the city as well as the design of housing for government employees, schools, shopping centers, and hospitals. All in all, an enormous undertaking.

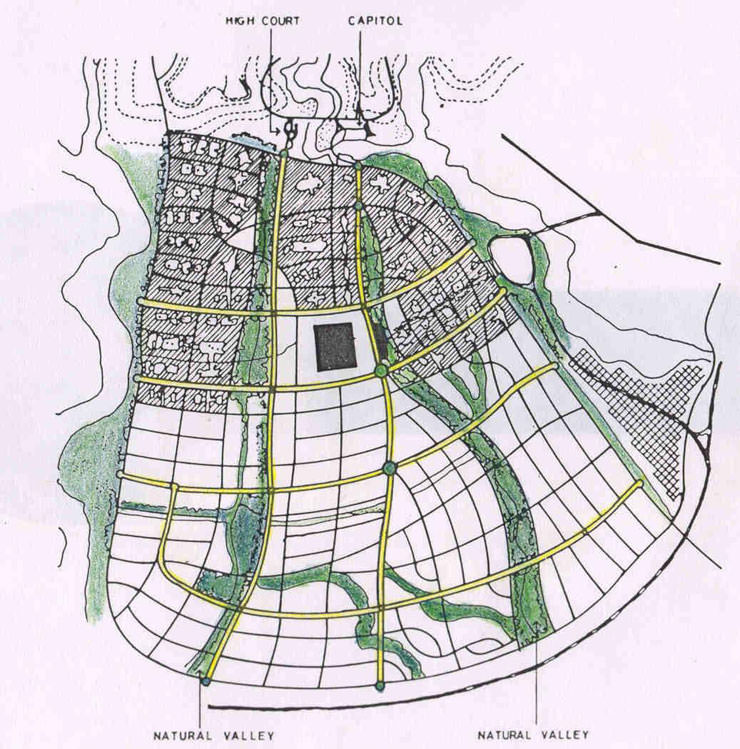

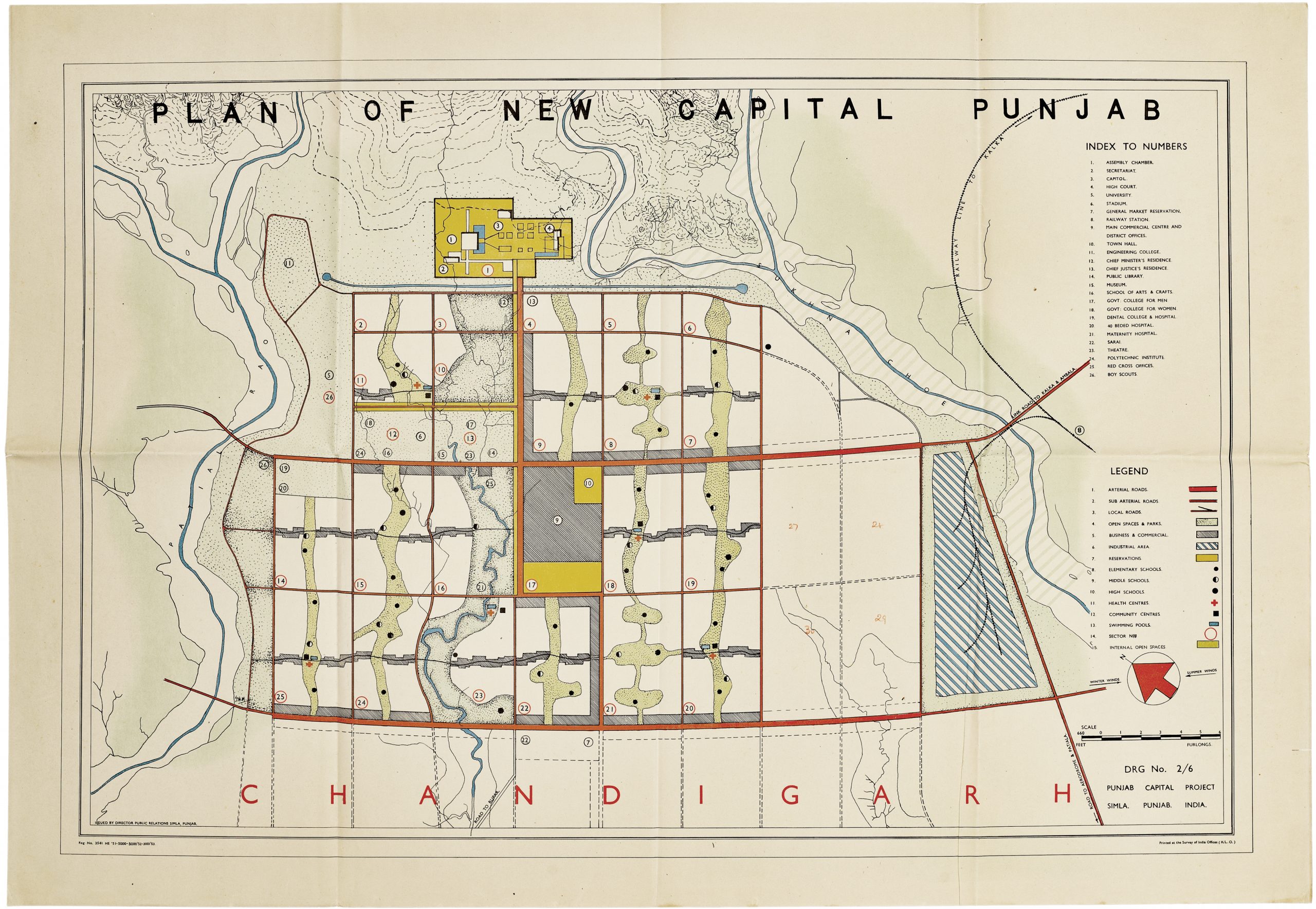

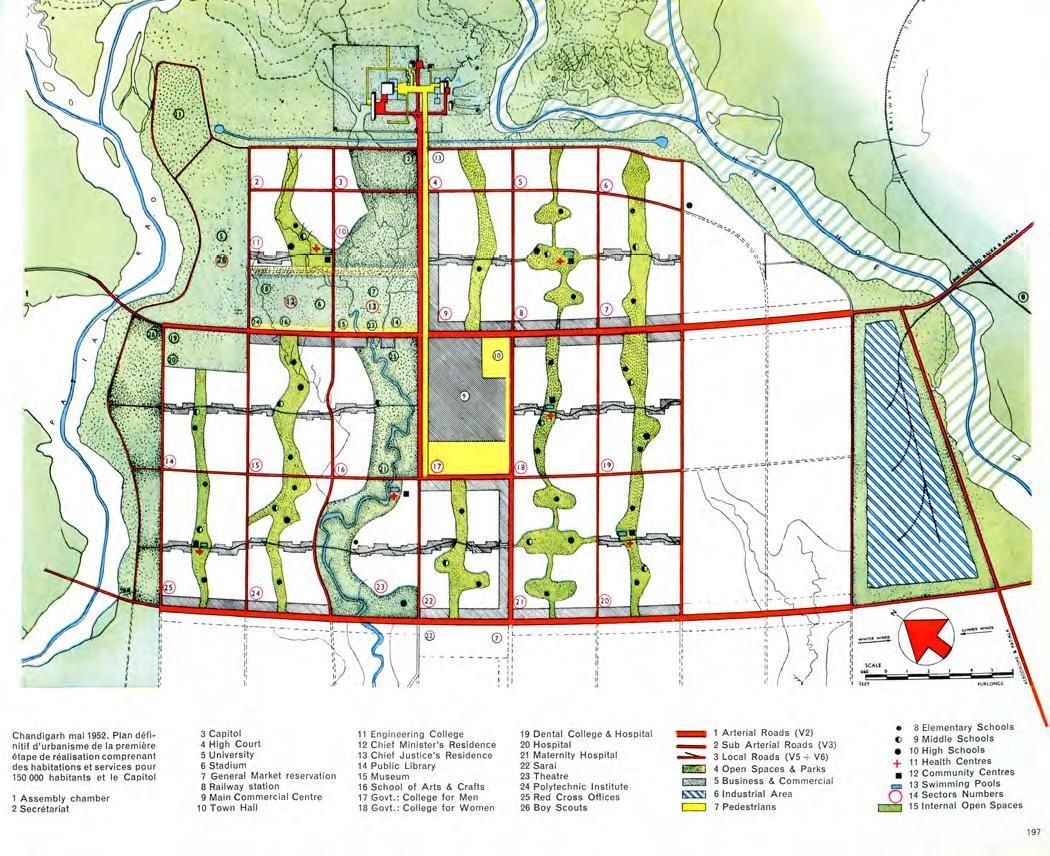

Corbusier’s plan for Chandigarh, which was based on the groundwork laid by Mayer, envisioned a city made up of residential “Sectors” (26 off them in the first planned phase) each with its own shopping center, health center, schools, parks, and internal circulation routes. Each Sector, measuring 800 meters by 1,200 meters, is surrounded by larger high-speed roadways with only limited access (one vehicular access point at the center of each side of each Sector), which serve as higher speed transportation between the Sectors with traffic circles at each intersection of roadways. Unlike Corbusier’s Unite projects, low-rise but more densely packed residential structures were envisioned.

Corbusier’s master plan for Chandigarh varied from Mayer’s in that the Sectors are smaller than Mayer’s “Superblocks” and where Mayer envisioned a more organic “fan” shape with curving roadways, Corbusier adopted a pretty rigid grid which also served to reduce the area of the city for reasons of economy.

Within this fairly strict grid, Corbusier strung together green areas and parks creating larger green zones which flow through the city and provide relief from the more rigid roadway grid. Within the overall layout of the city there are also sectors identified for centralized facilities which for Corbusier (who was big on anthropomorphism) are analogous to parts of the human body with Capital Complex as the Head, the City Center as the Heart, the green zones as the Lungs, the cultural and educational institutions as the Intellect, the network of roadways as the Circulatory System, and the Industrial Area as the Viscera.

For me, Chandigarh represented the intersection of a number of interests which are rooted in the last 45+ years of being educated and practicing as an architect and planner. I (like, I believe, most architects alive today) hold Le Corbusier and his work in pretty high regard but I have only actually seen one of his buildings – the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard – his only building in the U.S. So, needless to say, I was very excited at the prospect of actually seeing the amazing buildings of the Capital Complex which I had held in awe as a student.

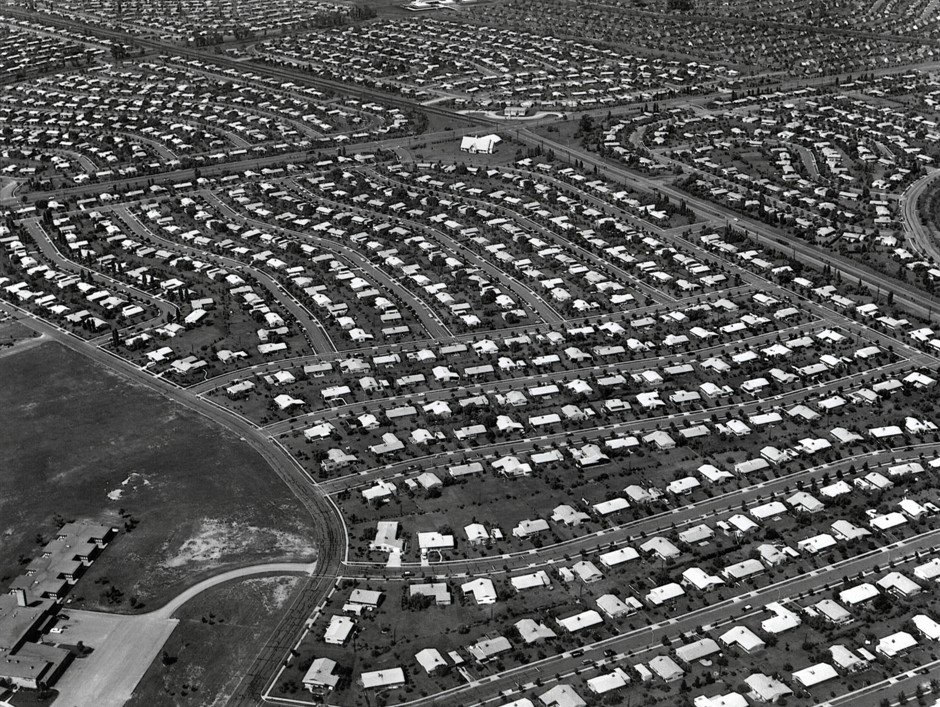

Also like many of my fellow architects, I am painfully aware that while the Modern Movement in architecture has resulted in many beautiful buildings, it has, when applied at a large urban scale, also resulted in some real disasters which have at times gone beyond just dead urban spaces. (If you’ve never heard of it, Google “Pruitt-Igoe” to see what I’m talking about here.)

I’ve also had the opportunity over the years to visit a few American “New Towns” (places which, like Chandigarh, were planned from scratch) and have found most of them to be rather lifeless places.

So, I was also very keen to see how well the plan for the City of Chandigarh actually functioned and, some 70 years after its construction began, whether it had resulted in a “livable” city.

Chandigarh (The Reality?) – Sector 15

I arrived in Chandigarh late on the evening of Saturday October 14th and got my first glimpse of Corbusier’s influence in the concrete canopies at the Chandigarh airport. My stay began with a little bit of confusion when I realized that the apartment which I would be staying in was actually in Sector 15 rather than in Sector 17 as had been indicated in the booking.

I quickly learned that the first question a prospective tuk tuk or taxi driver will ask is “Which Sector?” (Kind of reminiscent of the old “I’m from New Jersey” “Which Exit?”joke.) Fortunately, my driver was able to help me sort it out and I eventually arrived at the place from which I would be experiencing Chandigarh for the next week.

The place was everything I had hoped for, but not much more. It was a third-floor apartment in a clean modern building in a row of similar clean modern buildings. The listing for the place made it sound like a homestay, but it turned out to be an Airbnb with three ensuite bedrooms and shared common spaces consisting of a full kitchen and a very large and very under furnished living-dining area.

I was fortunate in that there were no other bookings for the week that I was there, so I had the whole place to myself. My room was pretty spacious and quite self-contained and had a private bath with a very powerful ceiling fan which proved able to dry any article of wet clothing within an hour or less. The room also had a small balcony with nice views of the backyards of the neighborhood. The balconies were the best feature of the place and what time I spent there not sleeping I generally spent observing the comings and goings of the neighborhood.

Beginning the first night of my arrival, I made pretty much daily trips into the Sector 15 market district, usually in the afternoon or evening and was surprised at how busy a place it became after sundown and into the evening, with crowds of mostly young adults (but also older adults and families) shopping, eating, and mingling. The first time, I attributed it to being Saturday night, but was surprised to see that it continued pretty much unabated through the week until I realized that the Sector 15 market district extends to the main entrance of Punjab University across the roadway in Sector 14.

As it turns out (perhaps I could have known this before I got there), because of its proximity to Punjab University as well as other institutions of higher learning in Sectors 25 and 26, Sector 15 is a popular place for students to live, congregate, and socialize. One of Sector 15’s local markets (known as the “Student Market”) is reputed to be the absolutely least expensive place to buy t-shirts, jeans, and other student garb. This also explained the inordinate number of bookstores which I had observed in the neighborhood.

I spent a fair amount of time over the next week (mostly evenings) wandering around Sector 15 and got quite comfortable with the place. I walked past its various schools and other institutions as well as a number of residential neighborhoods which varied a bit in terms of the type of housing, and from what I could tell, the Sector was a mix of families, pensioners, and students which kind of had the feel of a college town.

One of the odd things I did note about Chandigarh was the apparent dearth of temples compared to other Indian cities we have visited. But according to Google sources, Chandigarh has somewhere between 250 and 750 temples but the one I passed almost daily in Sector 15 doesn’t come up on a Google maps search. My best guess is that they are there but (for whatever reason) not as prominent as they are in older Indian cities.

While the green belt in Sector 15 was not quite as plush as the rendered plans might suggest and large parts of it are enclosed as school yards, there were some nice public parks and green spaces and there were generally a lot of street trees which have been allowed to pretty much take over in some areas. (One of the few criticisms I have of this place is that the sidewalks were often deteriorated to the point where they were at least dangerous and, in some instances, inaccessible.)

I will say that because there were only four points of access to and from the surrounding high speed roadways (which is true of almost all Sectors) it did feel a bit like being in a walled citadel, but I’m not sure whether this is a good thing or a bad thing and it’s not is necessarily any different than the natural and man-made boundaries which tend to define many neighborhoods and cities.

Hard to say whether it was a fair representation of what living in Chandigarh is for everyone, but Sector 15 felt clean and modern (both literally and architecturally). Although there was a high degree of regularity in regard to the organization, massing, and scale of buildings, there was still quite a bit of variety in regard to color, texture, and finish materials. The architecture was pretty consistently Modernist, but not at all monotonous and from my travels around the city outside of Sector 15 (limited as they were) I would have to say that this appeared to be true for most of the city.

Traveling outside of Sector 15, the high speed roadways are not particularly friendly for either pedestrians or (apparently) wild animals. I found that walking along the high speed roadways wasn’t a particularly good experience in many areas, due in art at least to the size of the blocks (1.2 kilometers between intersections when travelling northeast and southwest). I pretty quickly concluded that Corbusier didn’t intend for people to walk between Sectors (although there were crosswalks) and that motorized public transport (tuk tuks for me, but there were buses) was generally the way to go here.

That said, on my first morning in Chandigarh I walked from my apartment to the Capital Complex via what is known as “Leisure Valley”, the largest of the green ribbons which cross the city. Leisure Valley which runs from the Capital Complex in the north to the far south corner of the city, follows the course of an existing rivulet (which Le Corbusier elected to follow and disturb as little as possible). I was surprised not only at what a nice walk this turned out to be but also at the variety of outdoor spaces and features which are scattered along its length, including creeks and natural wooded areas, gardens, playing fields, sculpture, monuments, and other structures.

I was amazed at how beautiful these areas were and how removed they felt from the city they are in the middle of, and, even being a Sunday, I was also pretty impressed at the number of people out and about and active in the park (presumably, just as Le Corbusier had intended). It was definitely one of the best urban parks I have experienced and I found it interesting to compare it to another great one, Olmstead’s Central Park in New York City and I have to say that I found the more natural meandering design of Leisure Valley which threaded its way through the city to be more appealing (as well as more safe!).

A Successful Modernist City?

Based on the week I spent living in Sector 15 (and with the proviso that life in Sector 15 may not be representative of what it is like to live in other Sectors of the city), I have to say that I was pleasantly surprised to find how livable the city of Chandigarh seemed to be. Within Sector 15, which I found to be vibrant and lively, virtually anything you might need for day to day life was within a fifteen to twenty minute walk (twenty for me as I lived in the far southwest corner of the Sector) while outside the Sector there was a wealth of recreation and cultural resources available within 30 minutes or less public transport time.

Chandigarh is held by many to be the most beautiful and (until recently at least) one of the cleanest cities in India. And, while this city’s roots are intertwined with some tragic events of the past, there seemed to be a real sense of optimism and pride of place among the people I interacted with. I was amazed that virtually everyone I had the opportunity to speak with for any period of time not only knew that Chandigarh was India’s first planned city (and were clearly proud of this fact), but also that its architect was Le Corbusier.

So, bottom line, I would have to say that Chandigarh is probably far and away the most rich and lively “New Town” I have visited and is justifiably a success for Modernism and for Le Corbusier. In recognition of this, the Chandigarh Capital Complex was specifically identified as part of the Le Corbusier’s body of work which has been granted UNESCO World Heritage status.

Chandigarh Architecture Museum

On my way back from my first failed attempt to visit the Capital Complex (see below), I walked along the southern edge of the Leisure Valley in Sector 10 where several museums are located including the Chandigarh Architecture Museum (also known as the City Museum) which I visited. The Museum building is an interesting little Corbusien concrete structure designed by Indian architect S.D. Sharma, who worked under Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeannerete.

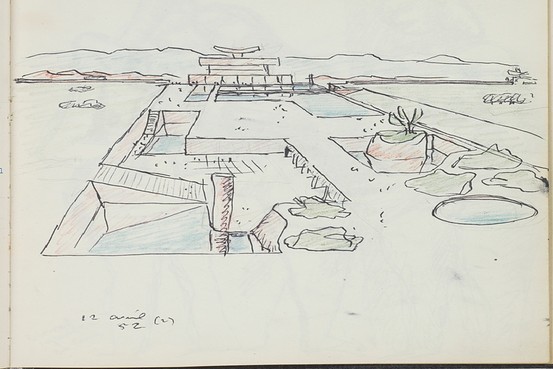

Originally intended to accommodate temporary exhibitions, the Museum was repurposed as part of India’s 50th Independence Anniversary in 1997 to serve as a repository for a vast collection of drawings, sketches, models, photographs, and other artifacts which do a great job of describing the planning and design of Chandigarh by first Mayer and then Corbusier and his team. A must-visit for architects and planners as well as anyone who is interesting in better understanding how and why Chandigarh came to be what it is.

Capital Complex

I tried to visit the Chandigarh Capital Complex on my first full day in the city, but discovered that (for security reasons) it is not open to the public and may only be visited as part of regularly scheduled guided tours, so I returned the next morning for the first tour of the day. Our group was very small – just myself, four Brits and their tour guide plus the Capital Complex tour guide and his assistant – which only served to emphasize the vastness of the plazas and walkways which connect the three major buildings of the Complex, the Palace of Assembly, the Directorate Building, and the High Court.

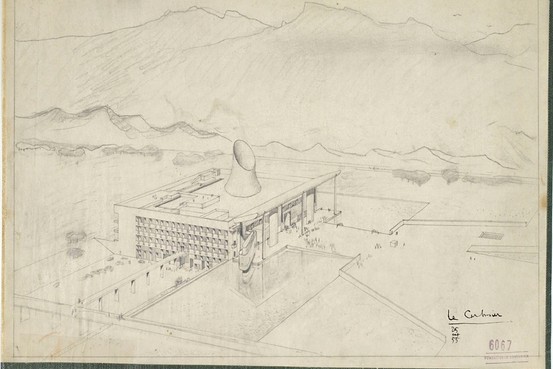

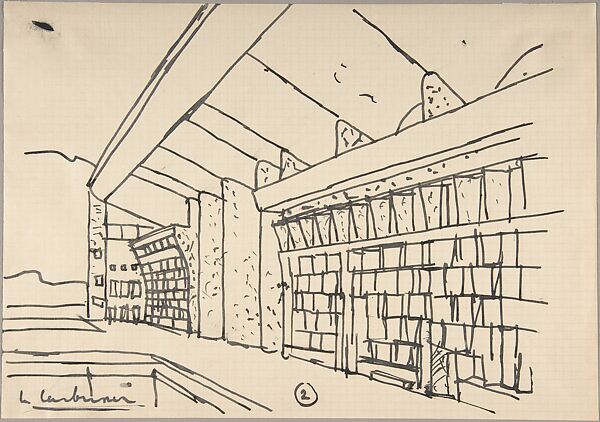

Corbusier’s sketches for the Capital Complex suggest that he didn’t envision it being quite this devoid of human life, but they do suggest that he envisioned vast monumental spaces which have often been the hallmark of bad Modernist urban design. But rather than dead urban spaces, the outdoor spaces of the Capital Complex were more akin to the Mall in Washington D.C. and their scale is intended to emphasize the importance and grandeur of the three major buildings of the Complex, the Palace of Assembly, the Directorate Building, and the High Court.

The Capital Complex grounds also feature a lake, reflecting pools, and four monuments including the “Open Hand” monument (actually a working wind vane which moves with the wind – who knew?) which has come to be known as the symbol of Chandigarh.

As they say, a picture is worth a thousand words, so here are a few thousand more words to describe this incredible place which sent shivers up my spine at times and took me back 45 years in time to my years as a student architect.

As a footnote I feel compelled to add that while Corbusier’s design of the buildings of the Capital Complex incorporated some pretty sophisticated ideas for solar shading and natural ventilation, he failed to anticipate that people’s tolerance would change as mechanical cooling became more common. Fortunately (or unfortunately?) his egg crate design of the façade of the Directorate provided an ideal arrangement for placement of the scores of outside condenser units serving the air conditioning systems which have been added over the years. You just can’t anticipate everything!

The Rock Garden

The other major site I saw in Chandigarh (had really not expected it to be so big!) was a rather odd place known simply as The Rock Garden of Chandigarh, a sculpture garden billed as being for “rock enthusiasts”. It is also known as Nek Chand Saini’s Rock Garden of Nathupur after its founder Nek Chand Saini, a government official who started building the garden secretly in his spare time in 1957. (Yes, really.)

It is a very large complex which can take quite a bit of time to get through as there is so much there. It begins with a series of narrow paths which pass through a variety of grotto-like spaces including man-made waterfalls, river valleys, and amphitheaters.

You eventually emerge into a village of sorts surrounded by a variety of whimsical structures which include an aquarium, a very odd museum with scenes of traditional Indian life, and a large play area with the craziest set of outdoor swings you can imagine.

All of this is constructed from stone, concrete, and a variety of recycled materials including old pottery shards which have been used to create some amazing tile work.

Along the way, here and there, are occasional humanoid sculptures which at first seemed just odd but progressed quickly to creepy and, in the final section of the garden, there are large assemblies of them (along with various animals) which more than anything reminded me of a scene from one of those brain-eating zombie movies!

A unique and amazing place, but give yourself plenty of time to get through!

Shimla Day Trip

As I mentioned at the start of this segment, my decision to visit Chandigarh was made in the hope of getting a glimpse of the Himalayas (or at least their foothills). I started by looking at what tours were available from Chandigarh and discovered the city of Shimla, about 75 miles north of Chandigarh in the (yes!) foothills of the Himalayas.

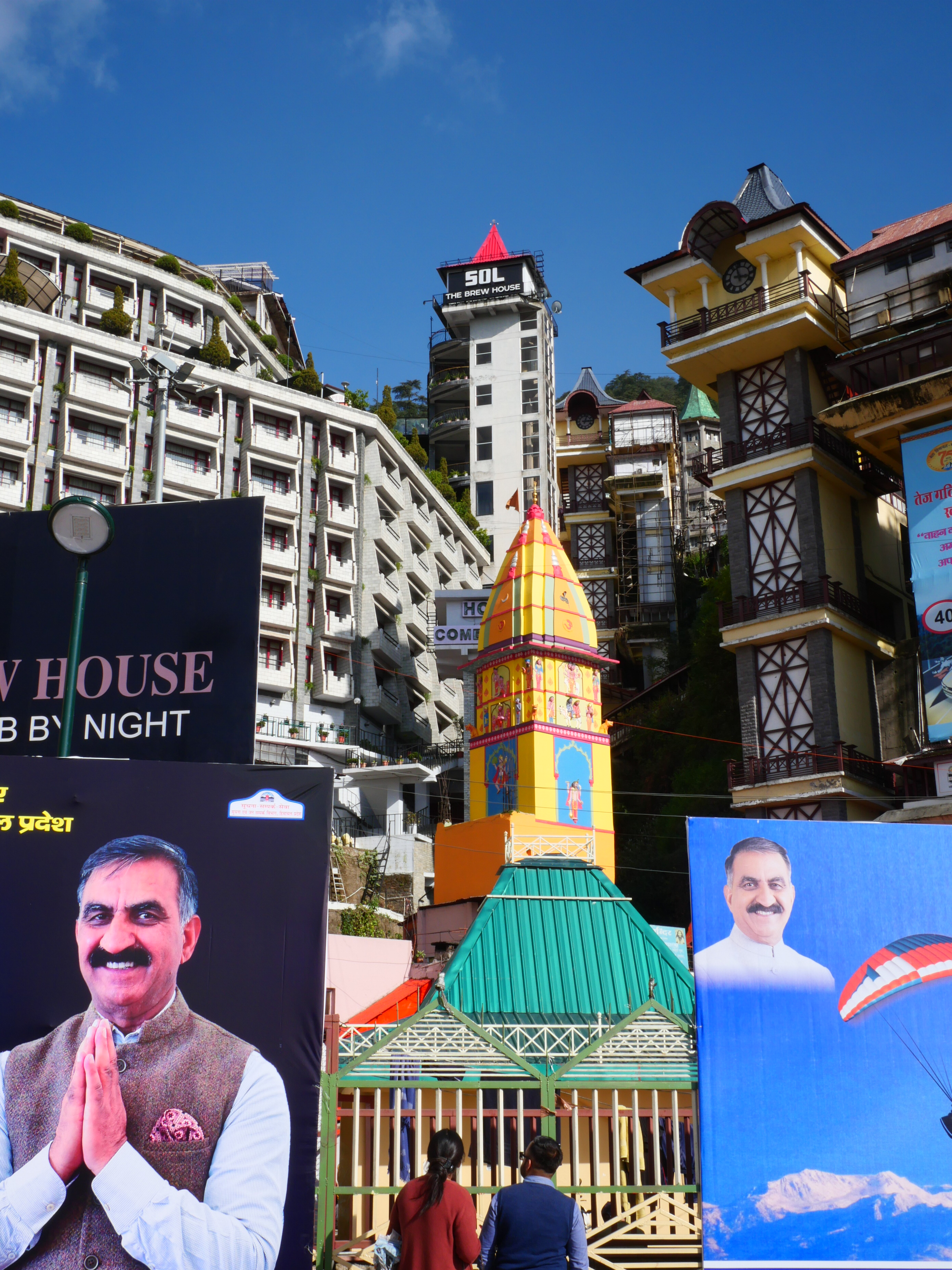

Shimla has quite an interesting history, including being declared the summer capital of British India in 1864 (when it was just too damn hot to be in Calcutta!). Since that time, Shimla has become an increasingly popular tourist stop both for its temples and for its infamous shopping streets (known as “The Ridge” and “The Mall”) which wind back and forth, seemingly for miles, across the steep mountain face upon which Shimla has been built.

After looking at tour options, I decided to book a car and driver for the day so that I could have as much control and flexibility as possible. My Airbnb host Nitsimran was able to recommend a driver and the cost was about the same as a guided tour with transport. I had done my own research on what to see in Shimla and set an itinerary and so wasn’t expecting too much in the way of guidance from my driver Jagdev, but he was (fortunately as it turned out) familiar with Shimla and the challenges of getting around it by car.

We left before sunrise as it takes about 3 hours to drive to Shimla from Chandigarh and I wanted to have as full a day as possible. The drive into the mountains as the sun rose with the fog still resting in many valleys was pretty spectacular and we stopped at a dhaba (the ubiquitous roadside café) for some masala chai and some breakfast and more amazing views.

Upon arriving in Shimla, my first stop was at the Viceregal Lodge, the former summer home of the British Viceroy, now a government office and museum. The Viceregal Lodge, now officially called the Rashtrapati Niwas (lit. ’President’s Residence’), is located at the end of a ridge on the aptly named Observatory Hill which commands wonderful views of the surrounding mountains and valleys with some nice walking paths and a very small but very nice rose garden.

The Viceregal building itself is a palatially large very well preserved example of the somewhat obscure Jacobethan style of architecture, which was quite popular in Great Britain at the time, which does seem like an overdone hunting lodge which perhaps speaks to Britain’s self image of its role in India at that time.

My next stop was at the Jakhoo Temple which is located at the top of Jakhu Hill, the highest peak in Shimla with an elevation of over 8,000 feet and on top of which is a 100-foot high statue of the Hindu god Hanuman (he’s the one that has sort of a monkey face). I knew that I wanted to go there but had become very confused and conflicting online directions and suggestions for how to do so, and this is where Jagdev’s knowledge of Shimla proved at least somewhat invaluable.

After creeping along the congested streets at the bottom of the city (most of the interior streets are closed to motor vehicles) Jagdev dropped me off at the end of a bridge pointing in a direction and saying something which sounded like “elevator”. Long story short, two elevators, lots of stairs and ramps, and one cable car ride later, I found myself taking in some amazing views of Shimla as well as staring 100 feet up to the pink smiling face of Hanuman.

My other identified stops in Shimla, which included the picturesque 1844 Christ Church were scattered along Mall Road and the Ridge and I spent what seemed like hours wandering those streets, looking in shops, and just taking it all in. Along the way I gave in to an undeniable urge and stopped at the Shimla McDonald’s for lunch where I discovered that in India a Big Mac is called the “Maharaja Mac” and is made with two chicken patties!

As I continued down, the streets became increasingly narrower and more crowded, and the stores changed from tourist shops to more local stores selling more practical goods and I honestly just kind of got swept away in it all.

After what seemed like (and actually was) hours, I found myself on a flight of very steep stairs then down one final crowded street and miraculously, I was back where Jagdev had originally dropped me off. I found my way to where he was parked and we managed to get out of town before the traffic went from bad to worse. Coming down from the mountains I again enjoyed the views and might have done a bit of napping on the way back to Chandigarh, where we arrived as the sun was just dipping below the horizon.

Moving On

As so often seems to be the case, my week (6 days actually) in Chandigarh flew by and before I knew it, I found myself in the back of a Tuk Tuk on my way to the airport in the dark before sunrise.

While I enjoyed my solo travelling time and the opportunity to indulge my architectural interests beyond what even Colleen (who is pretty good about such stuff) could tolerate, I was sorry that I had not been able to share some the places I had visited with her (she was actually kind of pissed that I went to Shimla without her), but I have this feeling that that opportunity will present itself again in the not too distant future.

Seriously, while I enjoyed the time away, I was really looking forward to being back together with my travel partner and what better place to reunite than in one of India’s most legendary and storied cities, the former British capital Kolkata (Calcutta).

So, until then, travel early, travel safe, and travel often.

Leave a comment